The Désirs & Volupté exhibition is being held at the Jacquemart-André Museumin Paris from 13 September 2013 to 20 January 2014 will then move on to the Chiostro del Bramante, Rome, from 15 February to 5 June and afterwards to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, from 23 June to 5 October 2014.

The Désirs & Volupté exhibition invites the general public to discover famous British artists of the reign of Queen Victoria, among them Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Sir Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and Albert Moore (1841-1893). The fifty paintings exhibited reflect the common desire of the artists to pay homage to the “cult of beauty” .

As the leading world power in the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), Great Britain paved the way for extensive economic and social upheaval. The artists expressed a sensual aesthetic with paintings offering a sharp contrast to the severity and moralising attitudes of the day: a return to Antiquity, interest in the nude, sumptuous decorative paintings, poetic as well as literary expression with medieval topics, a legacy from the Pre-Raphaelites.

The very essence of these artists’ work, who made beauty an absolute and an art of living, was to seek aesthetical beauty. Women were the main subject of this artistic style known as the “Aesthetic Movement”. Their bodies were no longer hampered as they were in everyday life but naked, symbolising a form of sensuous pleasure and feminine desire. Portrayed in a reinvented living environment, women are transformed into heroines from Antiquity or medieval times. Nature in all its abundance and sumptuous palaces serve as decors for these sublime, lascivious, sensual, amorous, kindly or evil women. Painting becomes a waking dream, with an abundance of symbols.

The paintings on show at the Jacquemart-André Museum, some of which are true icons of British art

(The Roses of Heliogabalus by Alma-Tadema,

Greek Girls Picking up Pebbles by the Sea by Leighton,

The Quartet by Albert Moore,

Andromeda by Poynter, etc.),

are part of one of the most important private collections of Victorian paintings: the Pérez Simón collection .

Painters Lawrence Alma Tadema, Edward Burne Jones, John William Godward, Frederick Goodall, Arthur Hughes, Talbot Hughes, Frederic Leighton, Edwin Long, John Everett Millais, Albert Moore, Henry Payne, Charles Edward Perugini, Edward John Poynter, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Emma Sandys, Simeon Solomon, John Strudwick, John William Waterhouse and William Clarke Wontner, emblematic of this Victorian period are represented through this exhibition.

THE EXHIBITION

At a time when British museums are rediscovering their Victorian painting collections, the Jacquemart-André Museum has also chosen to pay tribute to the great artists of this period through their celebration of feminine beauty. Offering a wide overview of British painting from the 1860s until the eve of the First World War, they all come from the Pérez Simón collection, which contains one of the finest panoramas of privately owned Victorian art.

Room 1 - Antiquity revisited

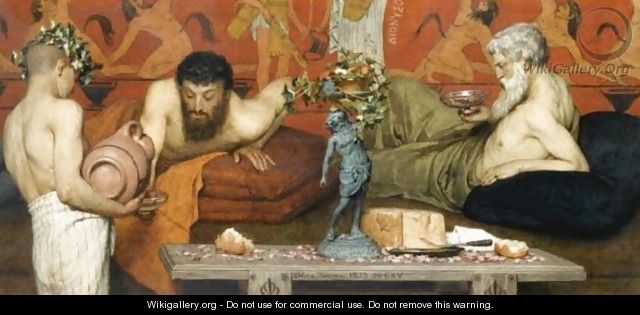

Centred on the emblematic figure of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, the first room in the exhibition reflects the strong enthusiasm for Antiquity shared by the Victorian élite. Thriving on extensive classical culture, the upper middle classes of the time had a passion for the archaeological discoveries made in Greece and Italy. The finest pieces arrived to enrich the British Museum collections and delight the London public. The extreme refinement of the decors revealed by the major excavation sites in Rome and Pompeii nurtured nostalgia for a golden age, an ancient world full of luxury and pleasure in landscapes enshrouded in sunlight. The artists who sought to bring this fantasy ancient world to life were therefore very successful.

As a result, Alma-Tadema became a favourite with collectors and was the most successful painter of his era. Of Dutch origin, he trained in Belgium where he acquired a taste for precision. He discovered Pompeii in 1863 and developed an enthusiasm for this new repertoire reflecting Antiquity that he reproduced to perfection

(Returning Home from Market 1865),

influenced by the French academicism and, above all by Jean-Léon Gérôme whom he met in Paris in 1864. Noticed by the very active Ernest Gambart, a Belgian dealer based in London, Alma-Tadema left Brussels for London in 1870.

Thanks to the historic accuracy of his reconstitutions, his sense of theatre and taste for decorative details, he was quickly very successful among the Victorian élite, captivated by the elegance and refinement of his paintings. He thus became one of the most active members of artistic society in London. While he mostly painted small size for the middle-class interiors of his contemporaries

(Greek Wine, 1873),

Alma-Tadema also painted a few exceptionally large paintings for his richest customers from 1885 onwards

(The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888).

Alma-Tadema stands out for the clarity of his compositions and his impressive technique. Whether representing episodes from history

(Agrippina with the Ashes of Germanicus, 1866)

to daily life

(An Exedra, 1871),

he constructed very structured scenes, playing on architecture and areas of shadow and light. A virtuoso, he devoted particular attention to the effect achieved when laying down paint and his ability to depict the brilliance of marble or the transparency of alabaster is unsurpassed

(An Earthly Paradise, 1891).

With

The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888),

he painted a masterpiece, the power of which resides in the combination of extensively rich decoration with strong dramatic tension.

Room 2 - Classical beauty

While Alma-Tadema successfully made use of a repertoire depicting Antiquity, other painters, such as Frederick Goodall (1822-1904) also devoted themselves to this theme, choosing to place representation of woman at the core of their artistic work. Their interest in Antiquity which they discovered during travel in Greece or Italy was reflected in their painting by a search for formal perfection.

While Alma-Tadema was excited by Greek and Roman Antiquity, Goodall’s passion was Ancient Egypt, discovered during a stay in Cairo from 1858-1859. He returned there in 1870-1871 and his entire career was to be dominated by the representation of scenes from Egyptian life, nurtured with historic or biblical references.

The Finding of Moses,

which accurately depicts the architecture and decor of Egyptian temples as well as the flora and fauna of the Nile, is a magnificent example of his painting.

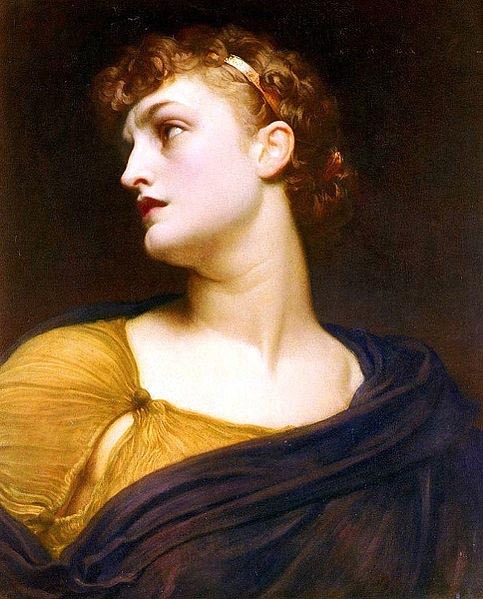

With their work echoing the theoretical debates taking place on the British artistic scene of the time, Frederic Leighton and Albert Moore stand out for the force and beauty of their compositions.

Frederic Leighton occupies a unique position among the artists of his generation. After training in Germany and Rome, he spent three years in Paris. Much impressed by the art of Ingres and academic painting in Europe, his work was entirely devoted to the search of formal beauty. He drew inspiration from a classical repertoire for his

Greek Girls Picking up Pebbles by the Sea (1871),

giving them a canon reminiscent of Roman scultpure. The dancing rhythm of his composition, the folds of fabric artificially lifted by the wind and the clever use of soft colours accentuate the decorative scope of the painting. In

Antigone (c.1882),

the palette is thicker. The artist emphasizes the sculptural nature of the composition by the twist of the bust and neck, giving the representation strong tragic intensity, directly inspired by classical Roman sculpture.

A solitary figure, Albert Moore was first of all influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Extensive study of Greek and Roman sculpture in the British Museum led him in around 1865 to develop a purely decorative style of painting, inspired by the Greco-Roman antiquity but without overly seeking historic truth. Drawing inspiration from Greek sculpture models, he upheld “art for art’s sake” and painted women with supple bodies, clothed in diaphanous drapes, emphasising their harmonious proportions

(Shells, 1875).

With the

Quartet (1868),

he devised his canvas as a painter’s tribute to music and, in an unusual manner, associated a Greek background with contemporary instruments. He thus developed an intellectual approach to painting, giving his composition a musical rhythm, visually suggesting a score and musical harmony.

Room 3 - Muses and Models

Despite the considerable influence of themes, the artists’ inspiration came also from the women, muses or models in their immediate circle.

Burne-Jones was part of the second Pre-Raphaelite movement but quickly set himself apart. Strongly inspired early on by literature, the artist cultivated a very personal style and a pronounced taste for English beauties with red hair, chiselled faces and long, graceful figures. This British charm had greatly captivated the Pre-Raphaelites and remained very popular with artists, as can be seen by the milky skin and leonine hair of the dreaming woman represented by Emma Sandys (1843-1876).

The figure of Pygmalion, to which Burne-Jones devoted several works, became an allegory of the artist for whom the ideal woman is one who inspires him, poses for him and is reinvented by him on canvas. Bessie Keene was one of the most important models for Burne-Jones. In the early sixties, he also used his wife Georgiana as the model as can be seen in

Fatima.

This practically unknown painting concentrated many of the sources of inspiration of Burne-Jones: the young woman with red hair and a very youthful face is wearing a Renaissance style dress, not unlike those that Burne-Jones discovered during his stay in Venice. True to his taste for a blend of the sublime and macabre, here the artist is illustrating the story of Bluebeard. He has grasped the crucial moment when the young girl is about to open the forbidden door. The soft calm of her face further highlights the dramatic power of the scene and arouses fear in the spectator, who knows how many bodies the young wife is about to discover.

Salle 4 - Femmes fatales

A topic developed by Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelites, the subject of the femme fatale, captivating, cruel, falsely ingenuous but a true enchantress is a frequent theme in British literature, starting with Shakespeare and brought back into fashion with the Gothic novel and poems of Tennyson. In painting, it was at its peak at the very end of the century, with its greatest representative, John William Waterhouse (1849-1917).

In the mid-1880s, Waterhouse endeavoured to revive Pre-Raphaelite themes, without however adopting their technique and keeping to a more academic approach. Fascinated by the myth of enchantresses, he created a very specific type of feminine beauty, with a long, angular face, slanting eyes and thick hair kept in place with a band. He used this feminine archetype in over thirty paintings, the subjects of which are drawn from Medieval literature, from Antiquity and medieval literature to Shakespeare. The expression of the girl, always distant, reflects the ambiguity of the character. In

The Love Philtre,

the woman, probably Medea, is questioning the spectator as she pours the poison into the cup. This sketch for a painting now lost, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1914, reflects the combination of an eminently classical theme with a free, very modern touch.

Room 5 - Romantic heroines

As well as in France, the Middle Ages were a subject very much in fashion in British 19th century literature, both in the Walter Scott’s novels (1771-1832) and in the lyrical poetry of Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892). In the 1850s, the Pre-Raphaelites made British classical or contemporary literature one of their main sources of inspiration. The artists of the next generation were, in turn, also to draw inspiration from it to develop a new aesthetic repertoire.

John Everett Millais (1829-1896) was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. After the Pre- Raphaelite group split up, he remained true to some of their themes, giving a romantic feeling to his compositions, such as in

The Crown of Love (1875).

Here, his subject is taken from a poem by George Meredith (1828-1909) published in 1851, inspired by the tradition of courteous love. Millais, a great lover of Scotland, situated this episode in a typically Scottish autumnal landscape which intensified the romantic scope of the subject.

Alongside Millais, Arthur Hughes (1832-1915) enthusiastically adopted the artistic programme of the members of the young Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood whom he met in 1850. Throughout his career, he remained true to the subjects of the first generation of Pre-Raphaelites, such as the Arthurian tales. In 1862, he took inspiration from The Marriage of Geraint, a poem by Tennyson, to paint

Enid and Geraint

which relates the story of a knight at the Court of King Arthur who made a love match when he married the daughter of a ruined lord.

Shakespearian plays were also a source of inspiration for Victorian artists. Choosing a verse from A Midsummer Night’s Dream as the title, Talbot Hughes (1869-1842), in

The Path of True Love Never Did Run Smooth (1896)

gave his work exceptional delicacy, both in the shades of colour used and the gracefully melancholic aspect of the young woman.

Another “disciple” of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937) maintained the poetic approach at the core of the Pre-Raphaelite movement for an audience still interested in this type of work. He drew inspiration from a poem by Tennyson to give a unique vision of the figure from King Arthur,

Elaine.

But his sources of inspiration are varied and he also did not hesitate to dip into British 16th century painting and contemporary music for his

Song without Words (1875).

Room 6 - Ideal harmony

Strudwick worked for a long time in the studio of Burne-Jones. The two artists shared the same taste for literary or allegoric figures and refined, poetic compositions. Strudwick worked on each of his paintings for a very long time and favoured complex iconography

(The Ramparts of God’s House, 1889).

While still influenced by the visual universe of Burne-Jones, Strudwick developed a very personal manner. He adopted a technique characterised by a linear style, reminiscent of the first Florentine Renaissance, and by a certain air of melancholy, almost palpable in In the Golden Days. He paid meticulous attention to detail, particularly to the sumptuous drapery and refined accessories. He sometimes chose a rich, deep range of colours but above all, liked to work with lighter shades, in a soft harmony of coloured greys.

Much appreciated in the Victorian era by critics as famous as George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), Strudwick remains forgotten for a long time before being rediscovered today by collectors. Shaw particularly admired

Passing Days,

an allegory of the ages of life. The choice of subject, the melancholic, the impassibility of their characters and subtlety of the colours give this very personal work a symbolic resonance profoundly universal.

Room 7 - The delights of the nude

In the second half of the 19th century, the nude became a genre in its own right in English painting. The greatest artists devoted themselves to it and, as a result, the nude stood as a veritable discipline and no longer as a minor genre involving specialist painters. Paintings of naked women became prolific, mainly small sized works and the paintings from the Pérez Simón collection reflect all the nuances of the genre.

The tutelary figure of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Gabriel Dante Rossetti (1828-1882) drew his inspiration more from Renaissance Italy for his

Venus Verticordia (1867).

This highly sensual feminine bust is not a portrait but an allegory of seductive love, as shown by the apple and arrow, highlighted by the russet tones of the pastel.

But the nudes were generally linked to the classical tradition and could take the form of an allegory or a scene from daily life in Italy, Greece or the ancient Orient. After a stay in France, Edward John Poynter (1836- 1919), very influenced by Ingres, created a break with his

Andromeda (1869),

whose body is seen entirely naked.

With

Crenaia, the Nymph of the Dargle (around 1880),

Sir Frederic Leighto, who had also spent time in Paris, once again took up the idea of a female nude set against a landscape, developed by Ingres in his Source. While influenced by this subject and by the formal translation proposed by French artists, he gives it a typically British touch. In the tradition of the English nude started in around 1840, he gave a real face to this young red-headed woman with a supple, sensual body, draped in long transparent pleats reminiscent of the movement of the water in the background waterfall.

John William Godward (1861-1922) excels in this type of sensual representation

(In the Tepidarium, 1913);

he favoured more intimate scenes where the full sensuality of the body is revealed.

Room 8 – The cult of beauty

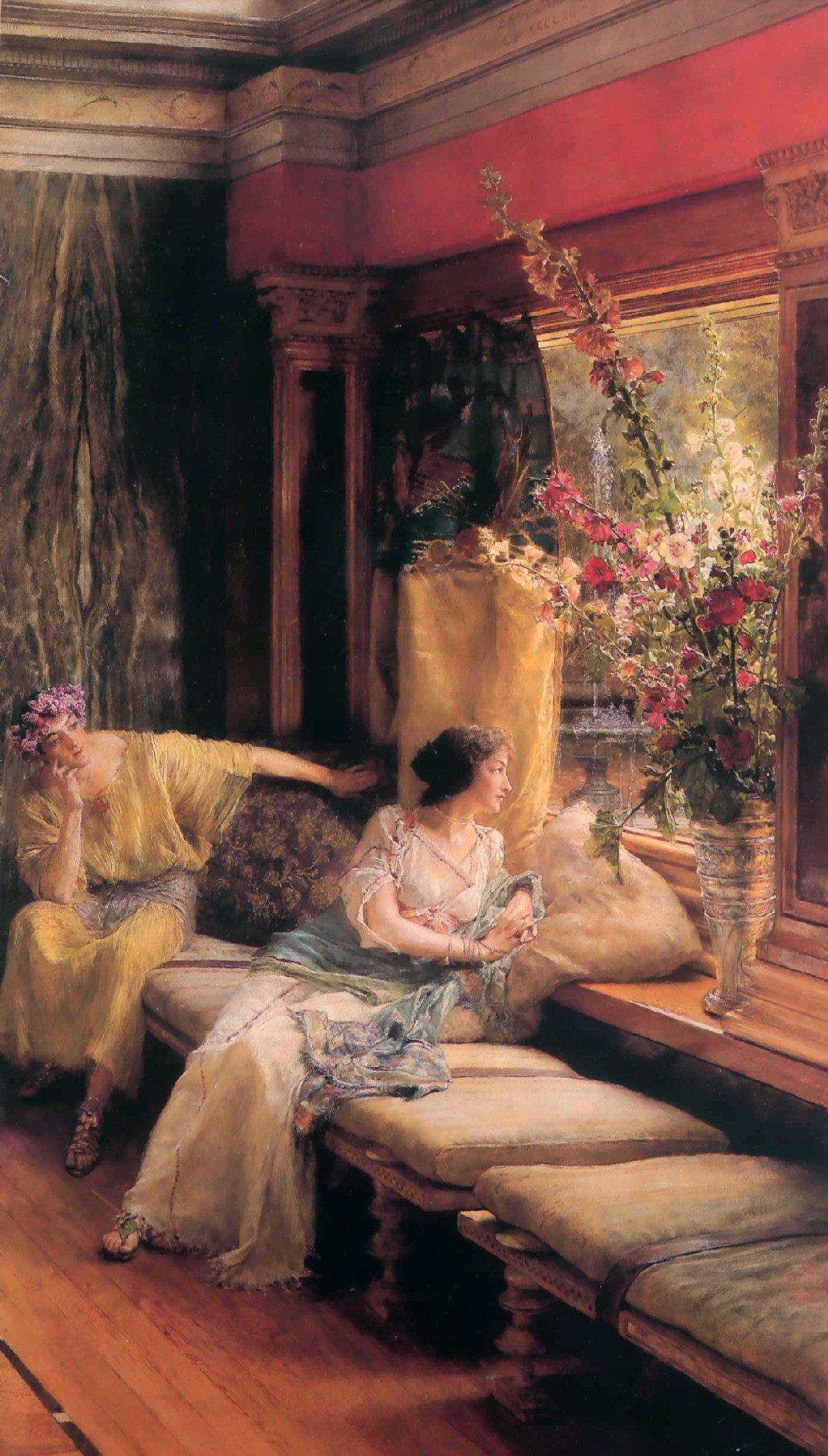

In Victorian society, all women had to be accomplished housewives. The woman who represented the ideal Beauty for this generation of artists, can only be seen in a universe dedicated to Beauty: her clothes, jewels and living environment must, by their elegance and refinement, reflect and sublimate her graces and virtues.

To meet the requirements of the industrial upper middle classes, architects designed and fitted out sumptuous interiors. The ornamental abundance characteristic of these homes was echoed by the major contemporary artists who, like Alma-Tadema or Leighton, decorated their houses with talent and profusion.

Elegantly clad and comfortably established in a magnificent décor, women escaped from daily life by dreams and romantic passion. These themes of heartache, longing and melancholy offered artists the means to combine poetry and painting by choosing a title for their works from quotations from Shakespeare or contemporary poets. Arthur Hughes and Charles Edward Perugini (1839-1918) favoured contemporary décors but Alma-Tadema on the other hand dreamed up imaginary interiors with a blend of ancient and contemporary details. These deliberate anachronisms give all their charm to paintings such as

Vain Courtship,

which, across the centuries, emphasises the eternal renaissance of romantic sentiment.

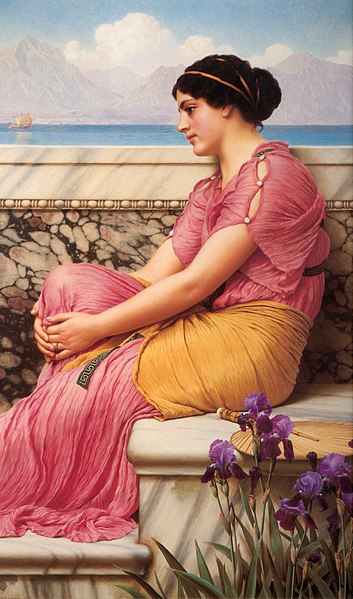

In a style close to that of Alma-Tadema, Godward also adapts the theme of feminine beauty to the classical ideal. His works are characterized by the classically clean drawing, harmony of the bright colours and precise way in which the paint is laid down

(Classic Beauty, 1908

and Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder, 1912).

While Antiquity was still one of the major themes for Victorian artists, they also enjoyed exploring other topics. The representation of women was still their main subject but with infinite variations. The magic of the East attracted painters who yielded to its enchantment, uch as William Clarke Wontner (1857-1930) with his

Soz Player (1903),

they depict British beauties with milky skin and sensual attire in sumptuous décors. Literary society that dreamt of a fantasy world developed a passion for these highly decorative paintings.

***

Moving between reinvented Antiquity, medieval legends and eminently British interiors of great charm, the major artists of Victorian England drew their inspiration from many sources but they all had one thing in common – the celebration of feminine beauty. In their works, the many faces of woman were the incarnation of all Victorian dreams.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dronjip, the Netherlands, 1836 – Wiesbaden, Germany, 1912)

Dutch by birth, Lourens Tadema trained at the Antwerp Academy of Fine Art before joining the studio of the Belgian painter and archeologist Louis De Taye, a specialist in paintings of the medieval history of Belgium and the Netherlands. He then became apprenticed to Henri Leys, one of the leading representatives of this historical and Romantic genre in line with the nationalistic aspirations of the young Belgium. At this point in time, the young painter added the family name of his godfather, Alma, to his surname to be well-positioned in catalogues.

His first visit to Italy in 1863, during which he visited Pompeii, his friendship with egyptologist, Georg Ebers and his meeting in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme helped him to gradually expand his subject repertoire to Greco-Roman topics. In particular, he excelled in the art of representing marble, wonderfully depicting its veins and transparency. He subsequently made several visits to Italy, enabling him to build up a remarkable collection of photographs of ancient remains and artefacts which nurtured the iconography of his paintings.

In 1870, he left Brussels and moved to London. Actively helped by the art dealer, Gambart, he soon achieved an important position in the social life of London’s artistic elite. He took on British nationality in 1873 and met with continued success in the annual exhibitions of London’s Royal Academy. His paintings which were then totally oriented towards Greek and Roman Antiquity, fully corresponded to the classical style and subjects of this institution, of which Leighton became the director in 1878: he was elected an associate in 1876 and an academician in 1879. He was knighted in 1899.

In the 1880s, he adapted his painting to the changes in taste, moving towards a slightly sentimental genre. In settings reminiscent of Antiquity, it took on topics with sensual, near-erotic connotations. In the last twenty years of his career, he turned towards portraits of personalities and theatre sets, giving free rein to his interest in the decorative arts. His death coincided with the end of an era of which he experienced the initial changes.

After achieving tremendous popularity in the late 19th century and then being heavily criticised during much of the 20th century, Alma-Tadema’s work enjoy now a spectacular renewed interest.

Frederic Leighton (Scarborough, Yorkshire, 1830 - London, 1896)

Leighton received an exceptional international training that was to influence his entire work and contributed to giving him unique status among the painters of his generation: he studied at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt-am-Main and under Nazarene painter, Edward von Steinle. Although he soon moved away from this initial influence, it gave him his first taste for historical subjects and opened up the doors to Italy where he lived between 1852 and 1855.

It was in Rome that he painted his first major success, Cimabue‘s Madonna carried in Procession in the Streets of Florence. (Royal Collection)

He then spent three years in Paris where, influenced by Ingres and artists of his generation, he devoted himself to classical subjects and nudes. This training in Europe was further complemented by travels in North Africa and the Middle East between 1857 and 1882, the decorative impact of which is clearly visible in the design of his London home in Holland Park.

Leighton returned to London to live in 1859 and became friendly with painters Rossetti and Burne-Jones as well as the writer John Ruskin. Apart from the domestic subjects common to his generation, his work was dominated by major classical themes, characterised by the restrained treatment of sentiments and the constant search for formal beauty. In the mid-1860s, the latter was expressed by the painting of several nudes of men or women and, in the late 1870s in a few major sculptures of men in energetic poses, directly inspired by Greek or Roman tradition (An Athlete Wresting with a Python, 1877, Tate). Despite the setbacks of his London debuts, Leighton was soon to become an associate of the Royal Academy (1864), an academician in 1868 and President in 1878.

Edward Coley Burne-Jones (Birmingham, 1833-London, 1898)

A dominant figure in British art in the second half of the 19th century, Burne-Jones took the painting of medieval enchantment of the Pre-Raphaelites to the obscure dreams of symbolism in an abundance of paintings. The son of a modest framer, whose mother had died in his infancy, he was an excellent pupil and, in 1853 became a student at Exeter College Oxford where he met William Morris who became a close friend.

From very different social backgrounds but both marked by the spiritual renewal of the Church of England, they were destined for priesthood. Influenced by the writing of Ruskin, they discovered their artistic vocation. Abandoning their studies, without diplomas or training but supported by Rossetti, they went to live in London, thus forming the nucleus of the second Pre-Raphaelites generation.

Burne-Jones’ extraordinary talent for drawing helped him to survive by notably working on designs for stained glass windows for architectural firms. Of his many visits to Italy between 1856 and 1862, it was probably the one to Venice and Milan with Ruskin that was to leave the greatest impression on his initial paintings.

In 1860 he married Georgiana Macdonald (1840-1920) who always supported him, despite his passionate adventures. A member of the Company created by Morris where he was responsible for stained glass windows, Burne-Jones soon attracted loyal customers, charmed by the poetic nature of his work.

After many years away from the public eye and several stays in Italy between 1871 and 1873, centred on Tuscany, Rome and the study of Michelangelo, he made a triumphal return at the first exhibition by the Grosvenor Gallery (1877) where he made his mark as one of the masters of the Aesthetic movement and one of Great Britain’s major artists.

The following decade was marked by a constant stream of ambitious undertakings and successes in England (with a first retrospective exhibition in London in 1892) as well as in the rest of Europe and the United States. In France, he was particularly admired among the symbolist circles. He was elected an associate of the Royal Academy in 1885 but scarcely visited it, resigning in 1893. He preferred instead the Watercolour Society or the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists. It was above all his work as a decorative artist, involved in all the domains of decorative art, including book publishing, that ensured his constant popularity. He would not have been able to continue all these undertakings without the presence of a studio which, with figures such as Strudwick, somewhat continued the “Burne-Jones” style, characterised by an exceptional sense of line and elegance in its colours.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (London, 1828 - Birchington on Sea, Kent,1882)

A founder member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood established in 1848, Rossetti brought to British art the originality of a character formed in a family rich in exceptional European literary culture. Resisting sound training in a studio or Royal Academy schools, he suffered throughout his career from a lack of technical training. However, without the constraints of perspective or the traditional cannons of anatomy study, his works were original in the extreme.

His involvement in the setup of the Brotherhood was above all expressed in the revolutionary claims of the movement against official creation. He was also the one to notice the promising talent of young William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, then students at Oxford. Refusing to exhibit in public, he became known to a wide-scale audience through his engraved illustration of an edition of Tennyson’s Poems (1857).

In around 1850, his meeting with model Elizabeth Siddal in the Brotherhood circle was to transform his life and art: she became his muse and mistress, then his wife in 1860 and mother of their only child who died at birth. She had delicate health and died in 1862 from an overdose of laudanum. The model for his female characters, she was the subject of a long series of drawings between 1850 and 1855 which played a decisive role in his drastic change of subjects in 1859. He devoted the rest of his career to representing female beauty.

In the mid-1860s, Rossetti enjoyed success with collectors and affluence. Afflicted by chronic insomnia as well as delicate physical and mental health further affected by drug addiction, his life became increasingly that of a recluse by the 1870s but still devoted to artistic invention. Exploring the relationship between poetry and painting, his last works explain the major impact that the retrospective exhibitions of his works organised in London just after his death had on the European symbolist movement.

John Everett Millais (Southampton, 1829 - London, 1896)

The youngest student ever to be admitted to the Royal Academy schools (in 1843), he took part in its annual exhibitions from 1846 onwards with traditional historic subjects. With Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, Millais was one of the three founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. His belief in the principles of the Brotherhood is particularly visible in his rejection of idealisation (Christ in the Carpenter’s Shop, Tate Britain) and his taste for minute, realistic detail (Ophelia, 1852, Tate Britain). This increased his popularity as an artist who liked to paint subjects from literature or national history. He was elected an associate of the Academy in 1853, becoming an academician in 1863. He also stood out for his wood engravings, illustrating poems by Tennyson (1857), books by the contemporary novelist Anthony Trollope or biblical subjects (Parables, 1863).

In the early 1860s, he turned sharply away from the Pre-Raphaelite movement of his youth, diversifying his subjects and drawing his inspiration heavily from the Old Masters of the 17th and 18th centuries: Velázquez, Frans Hals and Reynolds. His remarkable work as a portrait artist was inspired by these three Masters.

A happy family man, the very incarnation of a Victorian family life role model, he painted many portraits of children. One of the most innovative aspects of the latter part of his career was his approach to Scottish winter landscapes treated with a profound sense of naturalism. His exceptional popularity did not waver, maintained by his engravings and the demand from collectors.

Albert Joseph Moore (York, 1841 – London, 1893)

Born into a Yorkshire family of artists, Albert Joseph Moore studied at the London Royal Academy schools in 1858 followed by a long stay in Rome in 1862-63. Initially influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement, particularly in his treatment of biblical history, he produced huge murals and produced decorative objects, illustrations, wallpaper and stained glass windows, for William Morris in particular.

An in-depth study of Greek and Roman sculpture in the British Museum, combined with that of Japanese engravings, led him to develop a purely decorative style of painting, based on formal beauty, the musical rhythm of compositions and light, refined colours. This search for Art for Art’s sake, in which he played with anachronisms, leading him to the ultimate point of formalism, set him at the core of the Aesthetic Movement. He shared this approach with his friend the painter Whistler (1834- 1903).

His work, appreciated by several great amateurs throughout England, was regularly shown at the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery. He was however a very solitary person and was never elected to the Academy. His last paintings, making way for allegory and landscapes, sought to captivate customers looking towards symbolism or nature.

John William Waterhouse (Rome, 1849 - London, 1917)

The son of a second-category English painter living in Rome, John William Waterhouse was admitted to the Royal Academy schools in 1870 and made several trips to Italy until the late 1880s. During his entire career he regularly exhibited at the annual Royal Academy and New Gallery exhibitions. He became an associate of the Academy in 1885 and academician in 1895.

His first works were heavily influenced by Alma-Tadema and were devoted to the reconstitution of daily life in Antiquity. In the early 1880s, his work changed and he became interested in literary subjects, very popular with the first Pre-Raphaelites. He devoted his painting to the representation of women’s beauty, set in a moment of psychological tension. Literary heroines such as Lady of Shallott (Leeds Gallery of Art) mixed with enchantresses. He created several iconic images of femmes fatales of Victorian painting. His style, characterised by effects of atmosphere and extensive work on colour, showed a certain level of assimilation of more contemporary trends. His success came to a sudden halt with the advent of the First World War.

EXHIBITION CURATORS

Véronique Gerard-Powell, Senior Lecturer at the University of Paris - Sorbonne, is the Chief Curator for the exhibition. She spends her life between France and England and is responsible for teaching the history of collections at Paris-Sorbonne and the Abu Dhabi Sorbonne. She contributed to the editing of the Perez-Simon collection catalogue of Spanish paintings of which she is a specialist. She recently published a book entitled “Journey to Spain 1868 by Charles Garnier”, 2012, in collaboration with Fernando Marías, published by Nerea.

Also Curator of the Exhibition with her is Nicolas Sainte-Fare Garnot, Curator of the Jacquemart-André Museum.

CATALOGUE

The Jacquemart-André Museum and Fonds Mercator are publishing a catalogue for this exhibition. This work will be a historic landmark thanks to contributions by the Chief Curator, Véronique Gerard-Powell, and Charlotte Ribeyrol, Senior Lecturer in English Literature and Civilisation at the University of Paris – Sorbonne.

More images:

John William Waterhouse (1849 – 1917) A song of springtime, 1913 Oil on canvas 72 x 92 cm The Pérez Simón collection, Mexico © Studio Sébert Photographes

John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937) In the Golden Days , n.d. Oil on canvas, 66,5 x 46,1 cm Mexico, Pérez Simón Collection © Studio Sébert Photographes

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917) The Crystal Ball, 1902 Oil on canvas, 121,6 x 79,7 cm Mexico, Pérez Simón Collection © Studio Sébert Photographes

Henry A. Payne (1868-1940) Enchanted Sea, circa 1899 Oil on canvas, 91,5 x 65,5 cm Mexico, Pérez Simón Collection © Studio Sébert Photographes